At the Cornerstone of History and Faith

Antioch Missionary Baptist Church Celebrates 150 Years

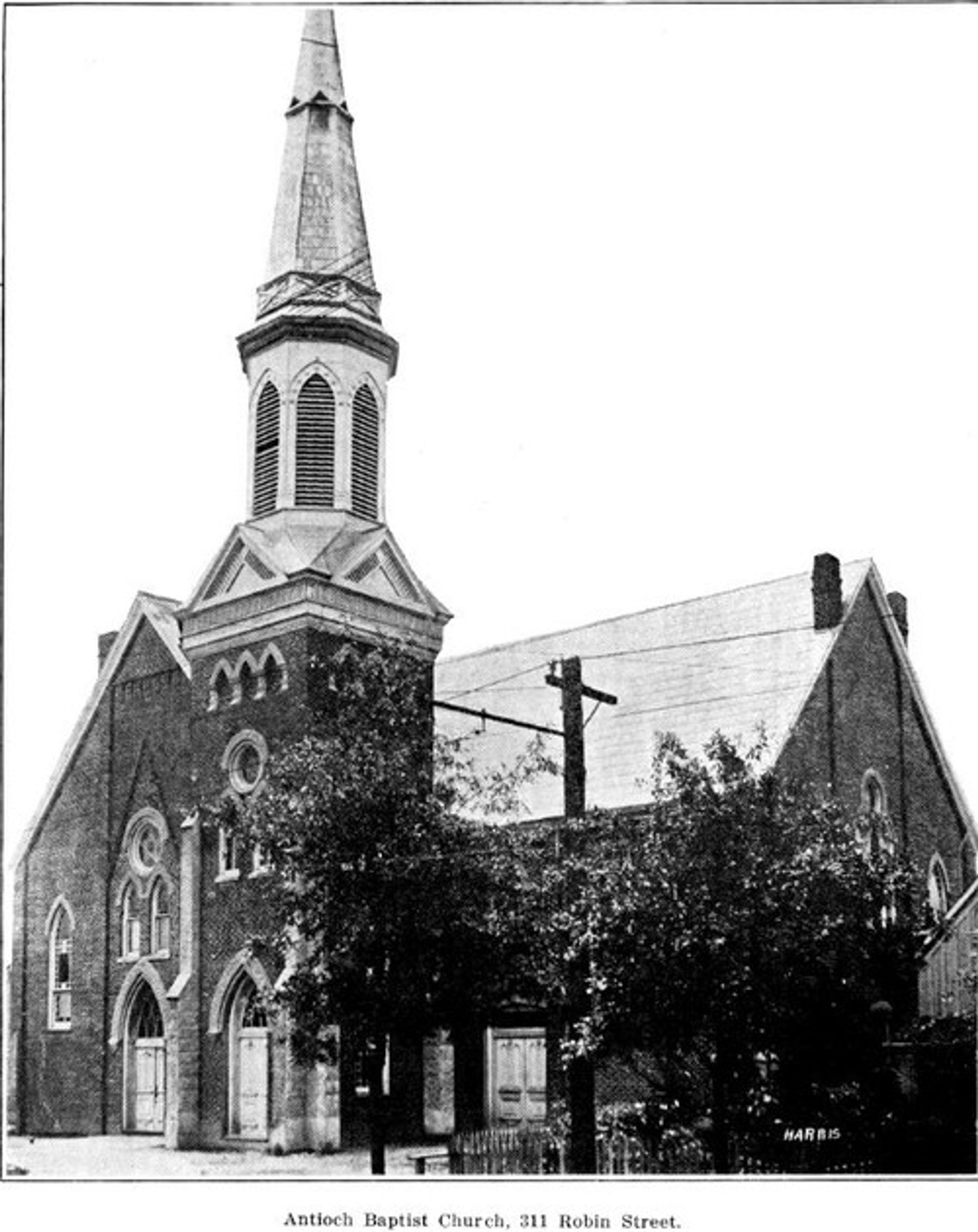

Nestled gently amid the towering concrete-and-glass skyscrapers that reach endlessly upward around it, Antioch Missionary Baptist Church clings to its roots in a city that is ever changing, ever growing, ever challenging itself to be a beacon of commerce and culture. Antioch issues no such challenges for itself. It doesn’t have to. It has a legacy nearly as old as Houston itself, and the principles that guide it come from a more powerful source than mere business.

Antioch understands its important place in the community. And, as the church celebrates 150 years in the city core, it’s sharing that story and inviting others to know what it’s always known: that faith surely moves mountains.

Bayou Beginnings

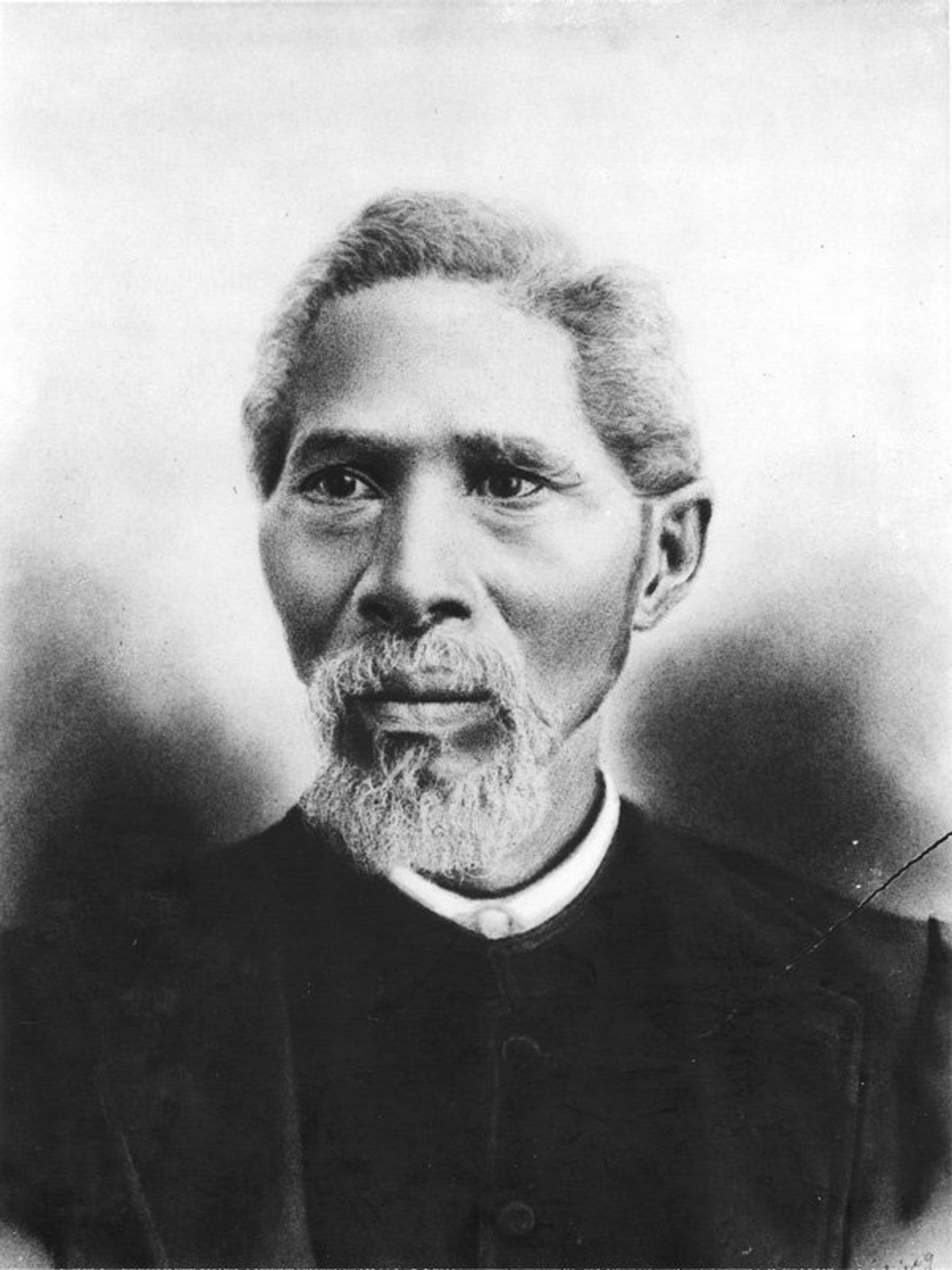

“This church is the story of a people who came out of slavery with only what they had on their backs, and they went looking for a new way of life,” said Jacqueline Bostic, the great-granddaughter of the Reverend John Henry (Jack) Yates, one of the original members of the church.

Like so many others who would come after them, they found that life here in Houston. And, like so many who came after them, they would build their dreams here.

In 1866, the country was emerging from the horror of the Civil War. The South found itself in ruins: grand plantations burned to the ground, cities destroyed, lives lost. While President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation freeing all of the slaves owned by Confederate landowners in 1863, many wouldn’t receive the news until 1865 after General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox.

For Texas slaves, that news came on June 19, 1865, with the arrival in the state of U.S. Army troops sent there to enforce emancipation and ensure the defeated South would once again find a way into the Union. Today, of course, we know June 19 as Juneteenth, and celebrations across Houston mark the occasion.

Freed slaves set out across the South, seeking a new life with this new freedom. One of them was Jack Yates. He had been enslaved in Virginia, where his mother looked after not only him, but his owner’s son. Jack and the boy grew up as friends and the boy taught Yates to read and write in secret. It was against the law for slaves to be educated, but this foundation would prove vital to Yates’ later life. He was freed in 1863, says Bostic, but then he did an odd thing.

“His wife was owned by a man who was moving to Texas, because Texas was holding onto slavery,” she said. “He got the slave master to agree to take him as well because he wanted to be able to care for his wife and family.”

It’s an extraordinary story of the extraordinary man who would be the pastor of an extraordinary church. Upon the ending of the Civil War, Yates assumed he would stay in the Matagorda County area, where he and his wife had been living with their owner. But the region wasn’t ready or interested in having blacks assume the full measure of society. Yates had heard that Houston was more welcoming, so he packed up his family and came north. Bostic says they settled on the banks of Buffalo Bayou. He worked as a drayman, hauling goods for merchants and shippers. Yates began to save his money, set on buying a home. And, on the weekends, he would bring fellow Houston settlers together to read the Bible.

Meanwhile, John Wheeler, Henry Stules, Edward Smith, Preston Greenhill, Daniel Riley, T.L. Brown, Sandy Parker, Wash Rhodes, Isaac Williams, Rhyna Moore, Margaret Jones and Cynthia Hill, all of them free slaves, founded what would become Antioch church on the banks of Buffalo Bayou. Assisted by missionaries from the First Baptist Church and the German Baptist Church, they built a “brush arbor” as their first worship space in January, 1866. The following spring, the community would build a more permanent structure on the corner of Rusk and Bagby Streets and christened it Baptist Hill. Reverend Israel Campbell led the group, which combined with other black Baptists to form The Old Land Mark Baptist District Association.

This is the association that would ordain Jack Yates as a preacher in the fall of 1868. Shortly after, he was named the first full-time pastor of Antioch Missionary Baptist Church. Under his leadership, the current church would come to be.

Building a Dream

Jack Yates proved to be a capable pastor and a man who knew how to get things done. In 1873, the church board of trustees was elected to purchase land and make plans to build a brick structure that would house the growing congregation. Richard Allen, who would later serve in the 12th Texas Legislature, was not only an Antioch parishioner, he would serve as architect on the project.

“People don’t really understand, but slaves built America,” says Bostic. “They had so many skills; they could do anything.”

And do they did. The present-day Antioch was built entirely by its congregation. Men made the bricks that would be part of the permanent structure, while the women of the parish helped doing everything from cooking for them and feeding them to looking after the children. They did all of this in their spare time while working at other jobs. The cornerstone for the church was laid in the spring of 1875; four years later, in August, the first service was celebrated in the first brick structure in Houston’s African-American community.

That would be enough of an accomplishment by any measure. But Pastor Yates knew the church could be much more than a place to gather for prayer and restore wounded souls. He wanted his congregation to be wholly integrated into Houston’s society. To do that, they needed to buy property. And to buy property, they needed to be educated. He set out to help them do both.

“Antioch Church was a beacon for our ancestors, a place of education and self-determination,” says Camilla Jackson, the chair of the church’s Heritage Committee, which is charged with collecting and preserving documents from the church’s founding, as well as sharing information about the church’s history with its members and the community at large. Her committee recently began donating documents to the African-American Library at the Gregory School and will continue doing so to ensure the church’s historic records are well-preserved and cared for. “And education was an extremely important component to the church’s mission.”

Realizing that education was a way to help the congregation thrive, the church’s first decades under Pastor Yates saw the establishment of the first kindergarten for African-American children, as well as laying the foundation for the city’s first high school for black students. Yates also helped congregation members secure loans to purchase homes and helped them learn how to manage their finances and set up businesses.

The Fourth Ward Comes into its Own

Antioch Missionary Baptist Church sits in Houston’s Historic Fourth Ward. Named to the National Historic Register in 1985, the Fourth Ward stretches southwest from Downtown’s core. Antioch Church would come to anchor the five-square-mile space called Freedman’s Town, so named for the freed slaves that established it.

“The church’s location is really vital to the civic activities that happened in Freedman’s Town,” says Billy Glasco, the lead archivist with the African-American Library at the Gregory School. “There’s a longevity to the church, and it helped the area grow.”

It’s almost impossible to imagine now, but 100 years ago, the streets around Antioch church weren’t crowded with skyscrapers and midrises; homes sprouted here, as did a multitude of black-owned businesses. From the 1870s to the 1920s, African-Americans were the majority population in an area that teemed with culture, commerce and a shared sense of community. At its heart was Antioch Church.

When the new brick church opened its doors in 1879, it was a cozy space done in the Gothic revival style so prevalent in the Victorian era. Evoking medieval design, the architecture was popular in the construction of churches, using castle-like towers and parapets in the design. Richard Allen designed all of these into the construction of Antioch, with its vaulted windows and rich interior. The pews were made by the congregation – in fact, the only restoration done to them was to add cushions and to refinish them in the 1930s – their dark wood a perfect complement to the sanctuary’s Gothic styling. In the 1890s, the church’s second story was added; 20 years later the church would expand again, adding west and south wings with meeting spaces and prayer rooms. African symbols adorn the doors of the church, which were donated by Memorial Hospital in the 1960s. Stained glass windows show Jesus holding a lamb in his hand, an eternal symbol of Christ as a living sacrifice. Over the church pulpit is a nut, symbolizing prayers and blessings to be bestowed on those who worship here.

The little church became an anchor around which the community grew.

“I can only imagine, after the assassination of President Lincoln, all the questions people must’ve had about the future, doubts about what it would hold,” says Otis Winkley, pastor of Antioch Church. “But they gathered together to build this church, and in doing so, they built this community.”

Winkley points to the church’s anchoring affect on the Forth Ward, noting the area was once teeming with houses, barber shops, businesses and office.

“The church ministered to the needs of the community,” he says. “It really allowed the community to grow.”

And it did grow. African-Americans poured into the area around Antioch, taking to heart the church’s mission to provide for its congregation. The early church leaders prized education and entrepreneurship; the Fourth Ward became home to centers of African-American education and several Houston-area schools and buildings are named for its early members.

“Various movers and shakers in the church were also prominent in the community,” says Jackson. “And it’s important for us to remember and document what they did.”

If Antioch was a community anchor, this was clearly a community with a proud and rich heritage. Booker T. Washington visited Antioch to speak. All the jazz celebrities came through Houston and played in clubs in the Fourth Ward. As Houston moved through its first 50 years, the Fourth Ward became a valuable, vital space in the city.

A Legacy Continues

“People don’t realize there is a thriving congregation here,” says Karen McKinney, the church’s business manager.

Today, nearly 500 members of the church worship, learn and provide assistance to the community around the small Gothic church. The church has a thriving scholarship program, a nod to its founders’ insistence on education and self-improvement. There are Wednesday evening bible study classes, as well as one on Thursday at noon, designed to bring in people from the surrounding office towers.

“I hope and believe that Antioch is a Downtown minister to the needs of the people,” says Winkley. “We want to be a blessing to those who live and work Downtown, and our doors are always open to those who need us.”

And this year, Antioch is loudly proclaiming the good news of its sesquicentennial. A series of celebrations are planned to mark the occasion, from family-friendly festivals on the church grounds to prayer services in the sanctuary and a huge gala at the Hyatt Regency. Those who work and worship at Antioch recognize that it’s special among city worship spaces. In addition to its storied history, many of the congregation’s members can claim ties to the original founding families.

Ross Hampton, one of the church’s members, believes they already have. Hampton has been a member of Antioch his whole life, and was one of the church’s scholarship recipients. Following his graduation from Prairie View A&M University in 2014, he came back to church to be a mentor to some of the church’s young men.

“Antioch was always key to my success,” he says. “I want to reciprocate.”

That feeling of reciprocation is one that’s echoed by members of the church. They feel a keen sense that they are standing on the shoulders of those who came before, who came to Houston seeking something more from life, thrived here and created a community whose legacy runs through the very streets Antioch stands on. There is a pride of history in their association with the church, but also a pride of place. They recognize that Antioch was born from the heartache and horror of slavery, but through faith and love, it has been a nurturing home where they believe God’s love surpasses all.

“I’m very proud of the fact that people who had nothing but such unbelievably hard times as we can’t imagine, had the thought and the will to come here,” says Bostic. “To know that you’re doing this for yourself after being told you have to do this because the master says, but you’re doing that for your family and your community and your people, you know you’re willing to make whatever sacrifices you have to in order to make this life happen. To me, that says people have a strength we don’t even know that we have.”

“Antioch is a symbol of permanence,” says Jackson. “These people who started the church were born in slavery. If people who were born as slaves can educate themselves and come together to build something permanent, surely we, who have all the benefits of this great society, can come together to help the community.”

As long as Antioch stands, its blue-and-white JESUS SAVES sign above the door, the members here promise they will continue the church’s legacy of providing for the community it serves.

“Our focus for the next 150 years will be the same as our first: to better the lives of the people we serve and to share the love of Jesus Christ,” says Winkley.

A Legacy of Community

In the shadows of Downtown, Emancipation Park is an enclave of green space in Houston’s Third Ward. Antioch Missionary Baptist Church Pastor John Henry (Jack) Yates, along with Elias Dibble, Richard Allen and Richard Brock purchased 10 acres at Dowling and Elgin and led the effort to create the park, joining forces with Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church to form the Colored People’s Festival and Emancipation Park Association in 1872. Members of the group pooled $800 to purchase the park land – making it the first public park in Houston. It was named in honor of the freedom the Emancipation Proclamation granted them.

The City of Houston acquired the park in 1918, and it served as the only public park for African-Americans. A community center was added as part of WPA project in 1939. Today the park is home to a swimming pool, playground, community center, ball fields and a picnic area. Emancipation Park received a State of Texas Historic Marker in 2009.

In 2013, the City of Houston and Friends of Emancipation Park broke ground on $33 million worth of improvements that are in the planning stages, including a new recreation center, enhancements to activity areas, turning the existing recreation center into a community center, and re-imagining the landscaping and entry. The newly designed park will not only strengthen the park’s historic ties to the city, it hopefully will create a catalyst for future neighborhood development.

A Legacy of Freedom

“The location of Antioch Missionary Baptist Church is a vital one for the city. Even with all the expansion and growth around it, all roads in Houston history lead to Freedman’s Town.”

That’s Billy Glasco, lead archivist of the African-American Library at The Gregory School. And he’s talking about an important Houston neighborhood: the Fourth Ward, which houses Freedman’s Town. Houston certainly wasn’t the first city in the country to have a Freedman’s Town; they dotted cities all over the nation, especially in the South, following the Civil War. Freed slaves settled these communities, giving rise to the moniker that they’d be known by. In these spaces, African-Americans build thriving centers of commerce, worship and modest homes, where they were free – literally and metaphorically – from white supervision.

Houston’s Freedman’s Town grew out of the Fourth Ward, which was created shortly after the city’s founding in 1836. Its boundary began southeast of the intersection of Congress and Main streets. The Ward’s boundaries travel along the banks of Buffalo Bayou, which is where Antioch Church was born. While initially there were more whites than blacks living in the Fourth Ward, as the 19th century wore on, more and more African-Americans settled into the area, creating a thriving five-square-mile space of businesses and homes. To say they built the area themselves is no exaggeration. The African-American settlers of Freedman’s Town paved the area’s streets with handmade bricks and constructed the buildings there themselves.

By the early 20th century, this enclave spread slowly out of the Downtown area (where present-day City Hall is located) and out past San Felipe Street (known to us now as West Dallas Street).

“This was the center of the first black educational and civic spaces in Houston,” says Glasco. “Many of the city’s first schools for African-Americans were built here. So were the first African-American businesses.”

African-Americans became prominent members of the Houston community. Antioch’s founder, Jack Yates, helped campaign for the first park for African-Americans, Emancipation Park, which would be constructed in Houston’s Third Ward. Yates was also instrumental in leading to the establishment of Houston College (known as Houston Baptist Academy), which opened its doors on three acres on the western edge of the Fourth Ward in 1894. The Colored High School, later renamed Booker T. Washington High School, was the only black high school in the Fourth Ward until the 1920s. Across the street from the school, a black branch of the Carnegie Library was constructed.

“Dr. Henry Lee built the first black hospital in Houston in the Fourth Ward,” says Camilla Jackson, chair of Antioch’s Heritage Committee, further explaining the significance of the area to the city’s history.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, by 1915 all but one of the city’s African-American doctors and dentists and three-quarters of Houston’s black lawyers had offices in Freedman’s Town. Before Texas Southern University moved quarters to its present-day spot, its forerunner, Houston Colored Junior College, was here as well.

Through the 1920s, the area was alive with African-American commerce and culture. Jazz clubs featured nationally known stars, the descendants of freed slaves bought and built homes, black business owners engaged in everything from the practice of law to teaching to running their own stores. But as the 20th century raged on, edging closer and closer to World War II, the city of Houston encroached on Freedman’s Town. New roads were built, and Allen Parkway Village was erected to house white defense workers. Following the war, Interstate 45 was constructed, and many of the Fourth Ward’s buildings were destroyed, fraying irrevocably the fabric of the once-thriving Freedman’s Town.

From a height of a population of 17,000 in 1910, by 1980 the population of the area had dwindled to 4,400, nearly half of whom were living below the poverty line. As Houston continued its ever-expanding growth, the Fourth Ward fell further and further into neglect. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the area began gentrifying, with many one-story, leaning shotgun homes replaced with the midrises and new businesses that would become part of present-day Midtown.

But the core of the Fourth Ward remains Freedman’s Town. And the echoes from this area built by freed slaves still linger. Freedman’s Town was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

Sesquicentennial Events

Throughout the winter, Antioch Missionary Baptist Church is hosting a series of events that celebrate the church’s 150th anniversary. Together, they honor the organization’s past and joyfully look forward to its future. They range from the secular to the spiritual, but all focus on the enduring legacy of the Antioch community. Worship services and church programs are open to all; the anniversary gala is a ticketed event. For more details, visit the church’s website: ambchouston.org

December 20, 2015- Youth Christmas Program

A celebration of the season with an emphasis on stories and song that are designed to appeal to the younger members of the parish. This family-friendly event is a holiday favorite.

January 15, 2016- Martin Luther King, Jr. Oratory Competition

Held in the church’s sanctuary, this annual competition for Houston elementary school students commemorates the life and legacy of the legendary civil rights leader. Judged by federal justices, lawyers and city luminaries, the fourth- and fifth-graders who take part are evaluated on their speaking skills and subject matter.

January 24, 2016- Family and Friends Day

Join the Antioch community for a celebration of the ties that bind us together. Food, fun and fellowship spotlight the event, and the welcoming atmosphere will make you want to save the date.

February 26, 2016- Sesquicentennial Grand Black-Tie Gala

Held at the Hyatt Regency Downtown, the gala is a glittering evening devoted to celebrating the milestone anniversary. Tickets are available through the church.

February 28, 2016- 150th Anniversary Worship Services

Offered in the morning and the evening, these Sunday services will pay special attention to the church’s history, offering thanks and praise for Antioch’s continued success. While Antioch is always open to everyone, the special nature of these anniversary services are an excellent way to learn more about the church, its mission and its members.

Mentioned in this Post

Antioch Missionary Baptist Church

500 Clay St